In Search of the Proto-Auto

Images: T R Raghunandan

Roughly equidistant between the more glamorous cities of Geneva and Zurich, Fribourg is one of the undiscovered gems of Switzerland. This little town is dominated by its University, which attracts a wide range of students from Europe and beyond, lending the city a multicultural air.

Much of Fribourg’s old quarter is situated on a promontory above the Sarine river. Not many visitors head for the riverside lower down, which is where local residents hold their flea market on the first Saturday of every month.

On the table next to an elegant elderly lady, the five colourful diecast and plastic models caught my eye. “How much are these?” I asked her. “Five francs,” she replied. That seemed reasonable, I thought, and handed over 25 francs to her. The lady raised her eyebrows in surprise. “They are all for five francs,” she said, returning twenty francs to me. I was overwhelmed and sat down for a chat. “Surely, these models were worth much more?” I asked. “I think it’s a steal for just one Franc each.”

“These belonged to my father,” she said. “He passed away a month back. I have no place for them and you look like you know their value. The money is not important; I’m happy they are going to someone who is happy with them.”

And happy I was, as I carefully wrapped up the models in soft clothes for the long journey home. These were most unusual models; manufactured in Italy by Brumm in 1:43 scale, they represented some of the earliest efforts at horseless land transportation, much before the internal combustion engine was invented.

Over a century before the Benz Tricycle put putted over the German landscape, inventors and innovators were attempting to use steam for land traction. The earliest model in my Fribourg collection is the Isaac Newton steam carriage.

In 1680, Isaac Newton prophesied that people would soon be able to travel at speeds in excess of fifty miles an hour, and suggested a steam locomotive that comprised of a spherical boiler mounted over a fire-grate, fitted into a four-wheeled carriage.

When steam was expelled from a movable nozzle, the carriage would move forward, in a simple illustration of Newton’s third law. While Newton made drawings of his steam carriage, it is not known whether he actually built a working version.

By the nineteenth century, steam traction was well recognised as feasible for both road and rail transport. Steam pioneer Richard Trevithick designed an experimental steam-powered carriage that ran in 1801, but caught fire when its drivers and passengers were in a pub celebrating the event. In 1802, richer with experience, he designed the London Town Carriage, which was mounted on enormous eight-feet-diameter rear wheels.

These wheels were driven by a geared transmission driven by a forked piston rod married to a single cylinder. The crankshaft drove the axle of the driving wheel. The demonstration run was successful, even though London’s streets were cleared for it. However, the lack of brakes led to the coach crashing into some railings soon thereafter, and it was then scrapped.

Onésiphore Pecqueur was one of the brilliant engineers who heralded the age of French enlightenment after the French revolution. Credited with the invention of the differential, in 1828, he invented the Pecqueur steam carriage. Up in front, the carriage ran off a vertically placed boiler, and the power was transmitted to the rear wheels through a single central propeller shaft.

By 1854, not long before the invention of the internal combustion engine, an Italian Army engineer, Virginio Bordino fitted a two-cylinder steam engine below a standard horse drawn landau, which drove the rear axle shaped like a crankshaft. A model of this horseless steam carriage is kept in the Museo Nazionale dell'Automobile Torino, in Italy.

Yet, the most celebrated of the proto-automobiles has to be Nicholas-Joseph Cugnot’s steam tractor, invented as early as 1769, even before the French revolution.

Paris in summer is crowded by tourists, and the post Covid rush was apparent everywhere, particularly at the Louvre and the other well-known museums. However, nestling in the quieter precincts north of the Louvre is the Musee de Arts et Metiers, less frequented by the run-of-the-mill tourist, but a Mecca for science enthusiasts.

Located in an old church, the museum is a celebration of France’s contribution to the advancement of science. Ecclesiastical architecture contrasts well with galleries that showcase measuring instruments of yore, Lavoisier’s laboratory preserved in its entirety, innovative construction techniques and even a display of electronics from the seventies.

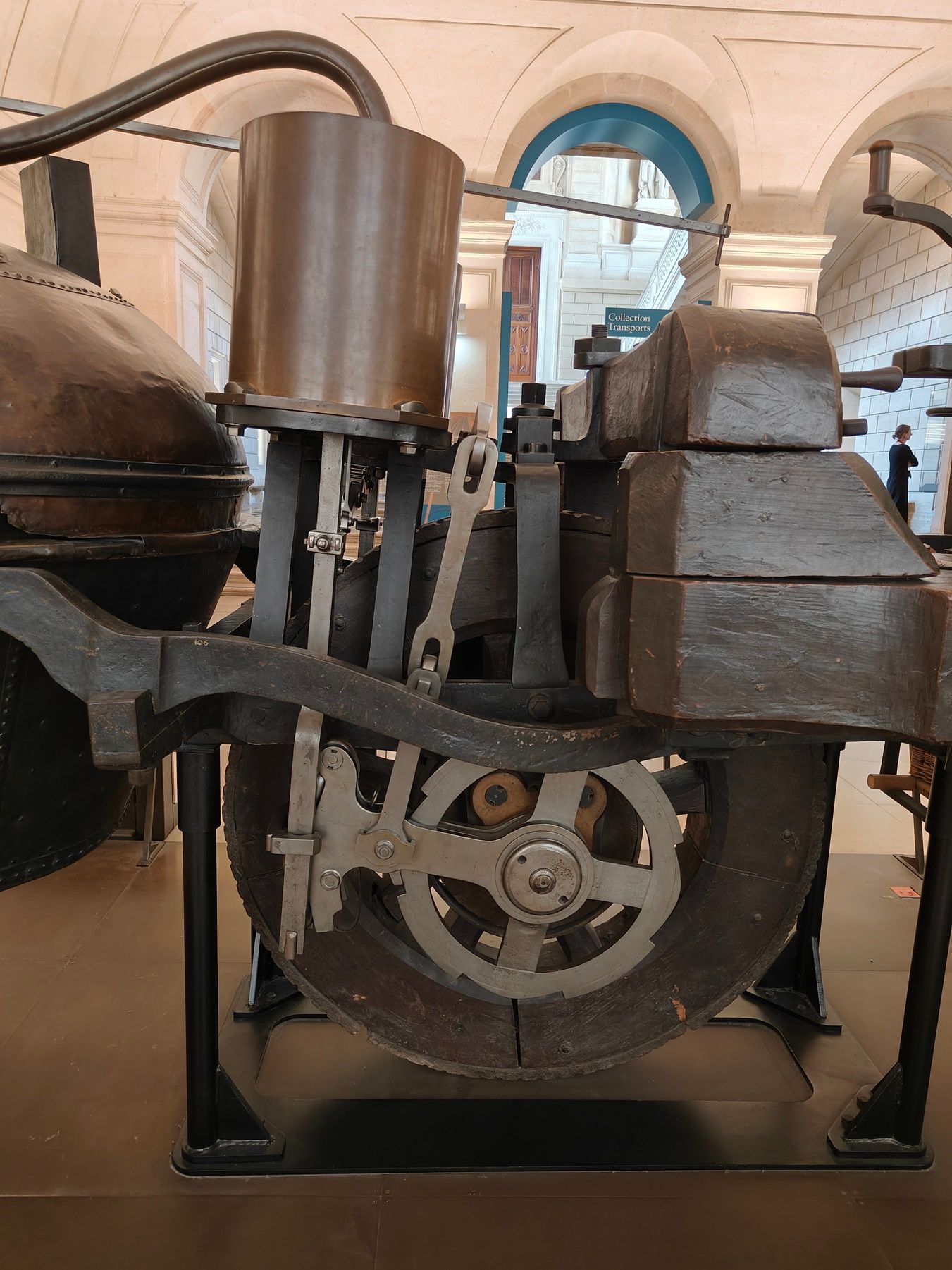

I did not intend to hurry through the museum, but looked forward in anticipation to the high point. Displayed in the cavernous gothic main hall of the church, below Bleriot’s plane in which he was the first to cross the English Channel by powered flight, stands Cugnot’s well-preserved Steam Tractor.

My first impression on seeing the tractor was how large and heavy it is. A three-wheeler, it was designed to pull heavy guns and for that purpose, it has a strong, wooden ladder-like chassis supported by two stout wooden wheels in the rear.

In front, cantilevered in front of the single front wheel, is the copper steam boiler, vaguely reminiscent of a traditional ‘Chembu’ from a south Indian kitchen. Steam from the boiler is led into two vertically mounted cylinders, from which pistons drive ratchets on either side of the single front wheel, transmitting its to-and-fro motion through a ratcheted wheel to the circular motion of the front wheel.

Reverence.

That is what I felt, as I looked at the silent monster and its muted wood and burnished copper, shining in the light of the tall windows of the church. Here is the precursor to one of the most revolutionary innovations that mankind has known, the ability to use mechanical means, not drawn by humans or animals, for propulsion.

Here is our holy grail. In the silence of the evening, I wondered how those innovators thought through their designs, drew them up and supervised the construction of these machines. Did they know how much their efforts would change our world?

Comments

Sign in or become a deRivaz & Ives member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.