Sailing With The Clouds And Other Heroic Efforts: Part 1

Images: Heritage Transport Museum, R K Sipani, Gave Cursetjee

There is a tendency to believe that the liberalisation of India’s industry began in 1991. Yet one must remember that it was in 1972 that the Indian government, under the prime ministership of Indira Gandhi, began the first wave of ‘liberalisation’ by providing more than two dozen new aspirants licences to manufacture two-wheelers.

The Government of India did one better, by getting into the business of making two-wheelers, by incorporating Scooters India Limited, which then went on to acquire the Italian Innocenti’s scooter manufacturing division (Innocenti had been making the world famous Lambretta range of two-wheelers since 1947).

Three years after its incorporation, production commenced at Scooters India’s Lucknow-based factory, with the first scooters, branded Vijai Deluxe, rolling out in 1975.

Amongst the many who decided to enter the ‘newly-freed’ sector of two/three-wheelers was Bangalore-based entrepreneur C Arunachalam. Having established successfully a dobbies and power loom manufacturing facility named Sunrise Industrials in 1957, Arunachalam decided to jump on to the two/three-wheeler bandwagon with a different kind of vehicle: a personal use passenger vehicle, unlike the commercial use auto rickshaws in vogue then.

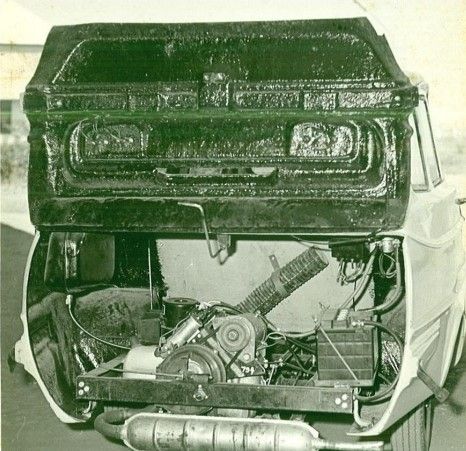

Thus, in 1972, he developed, on his own, a three-wheeler with a fully covered metal body and reputedly powered by a small two-stroke twin-cylinder engine. It is quite possible that Arunachalam used the two-stroke Innocenti Lambretta’s cylinder head and liner (which houses the ports) and made a new crank and block to design an opposed, flat twin-cylinder layout (with a slight offset in the cylinder axis), somewhat similar to BMW’s boxer-twin configuration.

As these cylinders must have been sourced from the Lambretta 150 scooter (which was being made under license by Bombay-based Automobile Product of India, better known as API), it is also possible that the 12bhp twin-cylinder engine was mated to the scooter’s four-speed sequential gearbox. With the powertrain located at the rear, behind the rear axle, the drive went forward to a differential, which powered the rear pair of wheels.

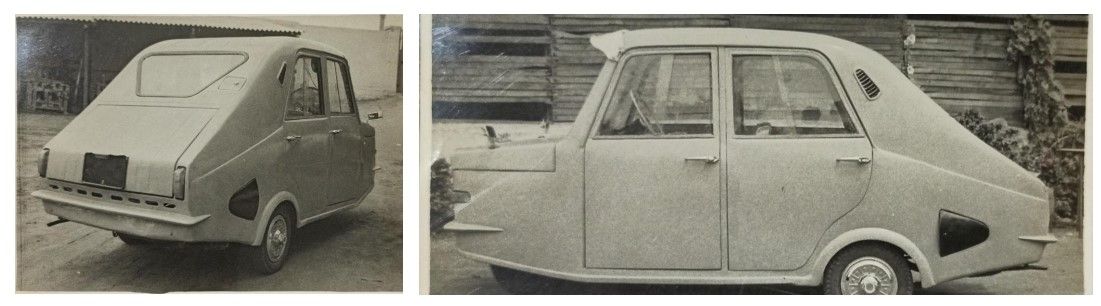

For manoeuvring the vehicle, a single wheel at the front did the job. Branded the Aruna, the four-door, four-seater three-wheeler prototype sported a rather strange metal body. Yet, the vehicle received a roadworthiness certificate from the Vehicle Research Development Establishment (VRDE), which allowed Arunachalam to successfully apply for and receive the license to manufacture the Aruna.

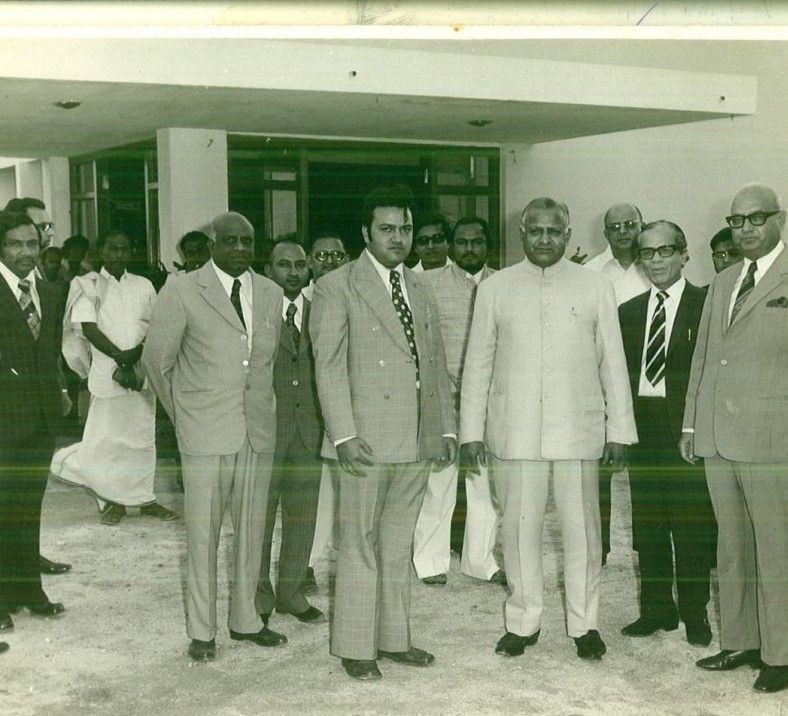

As always, making a prototype is not that difficult; getting it certified those days was easy, but getting the vehicle into series production was another matter. Not unlike the situation faced by the Indian Prime Minister’s son Sanjay Gandhi with his homegrown Maruti project, the industrialisation of the Aruna became a stumbling block, as the metal body needed expensive toolings; the transfer line required to manufacture the twin-cylinder also called for considerable investment. That was when C Arunchalam turned to timber merchant and Bangalore-based friend Ridh Karan Sipani.

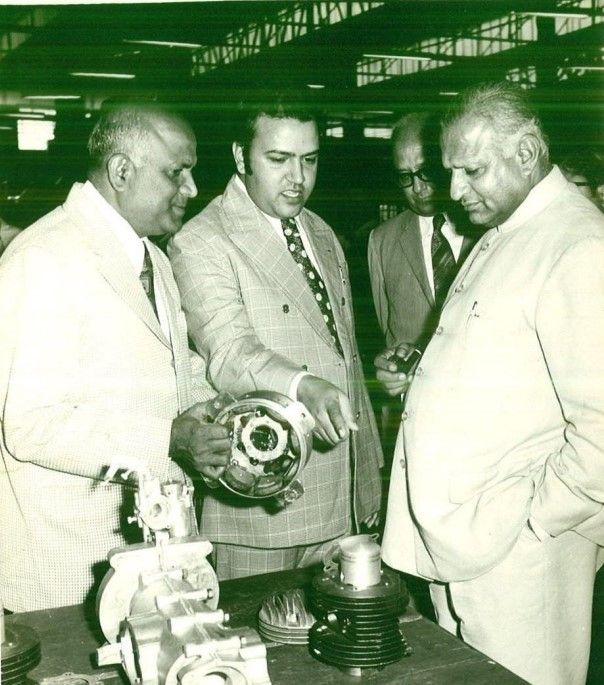

Not only did R K Sipani invest in the recently founded Sunrise Auto Industries Limited (SAIL), he also went about using all his contacts to bring on, as consultant, an engineering team headed by ex-API’s A Padmanabhan, as well as fibreglass expert Gave Cursetjee, especially after Fibreglass Pilkington came by offering their material and expertise.

Gave Cursetjee, also Bangalore-based, had developed a fibreglass body on the base of the Indian-made Standard Herald (the Triumph Herald made under license), and had sold some 36 of these Herald-based ‘sports coupes,’ badged Cobra, with the complete body in fibreglass.

Thus, whilst Padmanabhan and his team went about re-engineering the car and adapting the single-cylinder 198cc engine available from Scooters India, who were also commencing the production of the rear-engine Lambro three-wheeler branded as the Vikram, Cursetjee, given his experience, redesigned the body into a much smarter looking fibreglass shell with three doors: two on the left, kerb side of the vehicle, allowing for easy ingress into the (separate) front passenger seat, as well as the rear bench seat (which was designed to hold two comfortably), and just one on the right for the driver to enter and exit.

To give the body the necessary strength, Cursetjee used crease lines everywhere, designing an arguably handsome front end, an interesting six-window side profile with an excessive rear overhang, and a less convincing rear end, ruined by the engine door ‘hanging in’ there. Ventilation was by top-hinged flap style half windows, and flat glass was used throughout for the eight windows.

Padmanabhan designed a Y-shaped C-section chassis frame, suspended the rigid rear axle with leaf-springs/shock absorbers, and helical springs with telescopic shock absorbers for the single front wheel. The 15-litre fuel tank, located at the rear, directly above the engine, gravity fed the Spaco carburettor.

Although the engine had been ‘reduced’ to the 198cc single of the Lambretta 200GP/Vikram, the 10bhp power-plant was still good enough to propel the lightweight 450kg vehicle close to a claimed top speed of 75 km/h. “In fact, with the move to a fibreglass body and the ensuing lightening of the three-wheeler, the idea came up to brand it as Badal, or ‘cloud’ in Hindi,” points out Sipani.

So how did it work out for the Badal? Tune in tomorrow for the next part of the story, to find out more on the Badal adventure.

Comments

Sign in or become a deRivaz & Ives member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.