The Italo-Canadian Specialist That Refuses to Die

Text: Nigel Mathew Images: Reisner Family Collection

The Intermeccanica story began in 1959, when Hungarian–Canadian Frank Reisner became bored with his job of working as a technical paint representative for an American company in Montreal, where he and his Czechoslovakian–Canadian wife Paula were living.

The Reisners took a leave of absence and returned to Europe to visit various car manufacturers. They gained entry to Alpine, Citroën, DAF, DKW, Fiat Gordini, Panhard, Peugeot Porsche and Volkswagen while touring in their Fiat 500. This extended three-month automotive expedition lasted 18 years, and it resulted in the birth of the legendary Intermeccanica brand.

During their travels, the Reisners met American Richard Hatch, who lived in Rome. Hatch had built a very successful business manufacturing bolt-on speed equipment for Italian cars. Frank Reisner came to the conclusion that if he could build a business like Hatch's, he could live and work in Italy. The sale of his VW-based Devin Special back in Montreal supplied the cash to launch the business and register the Intermeccanica name, which was a modified version of Italmeccanica, an Italian company best known for its superchargers.

The company was registered in Montreal, and Reisner placed an advertisement in Road & Track. With two months lead time for the ad, the couple traveled to the Italian Riviera for a vacation. When they returned to Turin, PO Box 153 was full of envelopes containing orders, cash, checks and money orders. They were off to a quick start.

Intermeccanica ordered a full line of speed equipment kits, including bolt-on free-flow exhaust systems; the exhaust systems were available for 50 different models of European cars. They sold particularly well in South Africa, and in North America they were sold under the Stebro brand name, years before the famous Abarth systems were available.

After speed equipment, the next step was Formula Junior open-wheel race cars. Between 1961 and 1962, Intermeccanica built one complete FJ, along with 10 modified Peugeot engines for Illinois Intermeccanica distributor and speed shop owner Bill Von Esser. Having ventured into race car building, it was time for Intermeccanica to enter the world of sports car manufacturing with the Intermeccanica Puch, or IMP: It caused a big stir when it won the 500cc class at the Nürburgring, beating the well-established Abarth team. Carlo Abarth was outraged that the IMP won so he lobbied Flat to stop Steyr Puch from selling its modified Fiat chassis to Intermeccanica. Abarth's efforts succeeded, and the IMP project ended after just 21 cars.

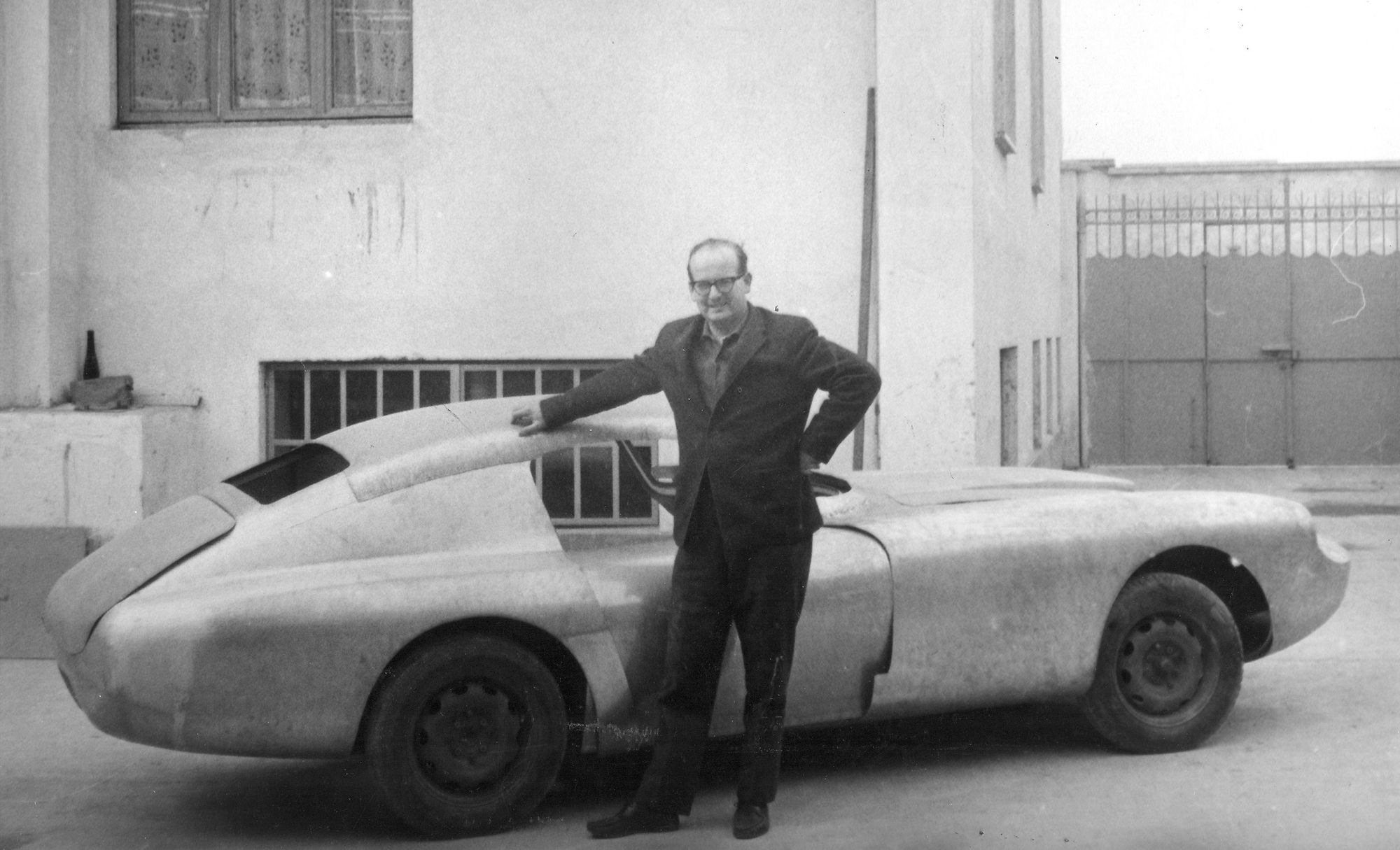

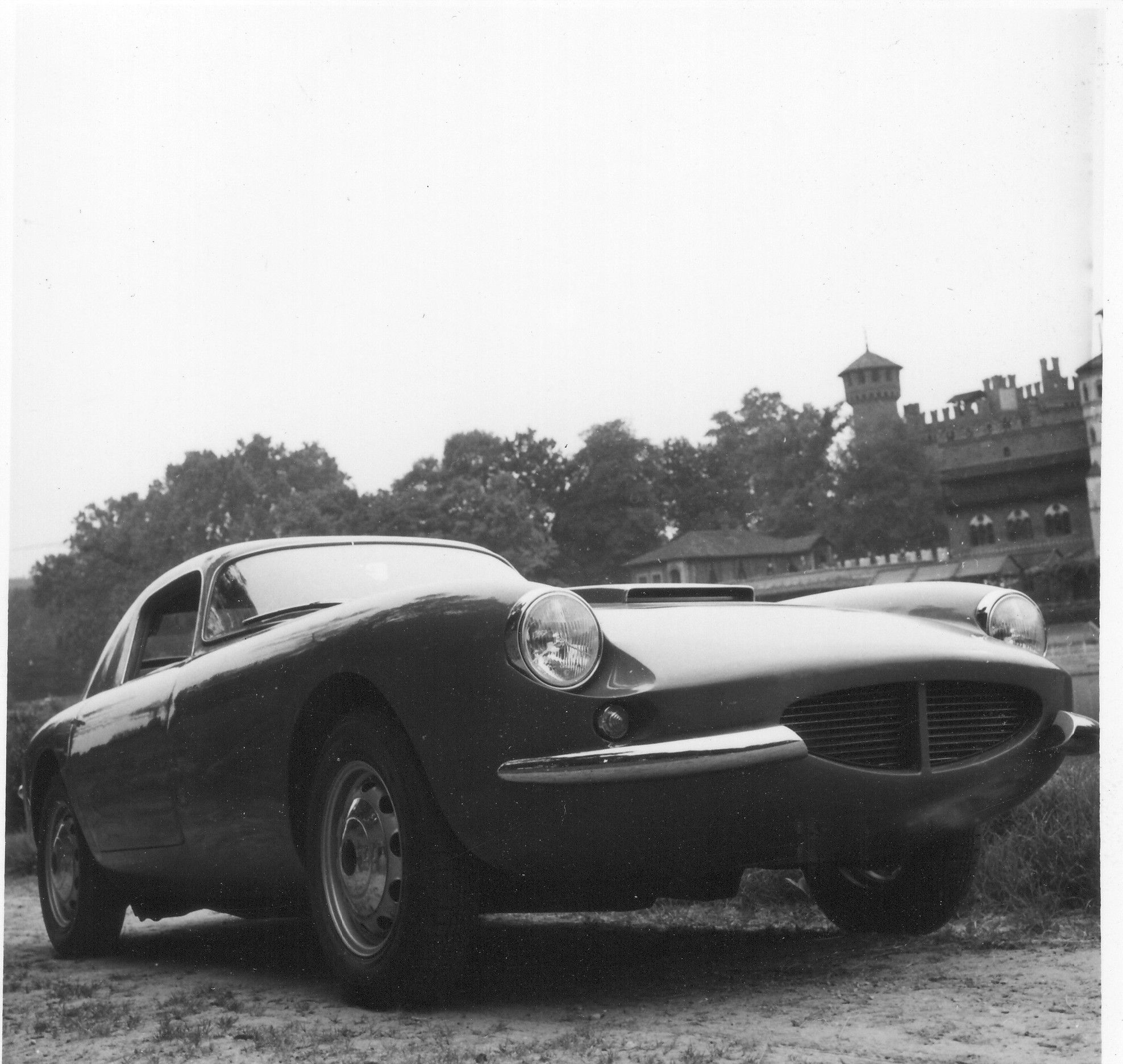

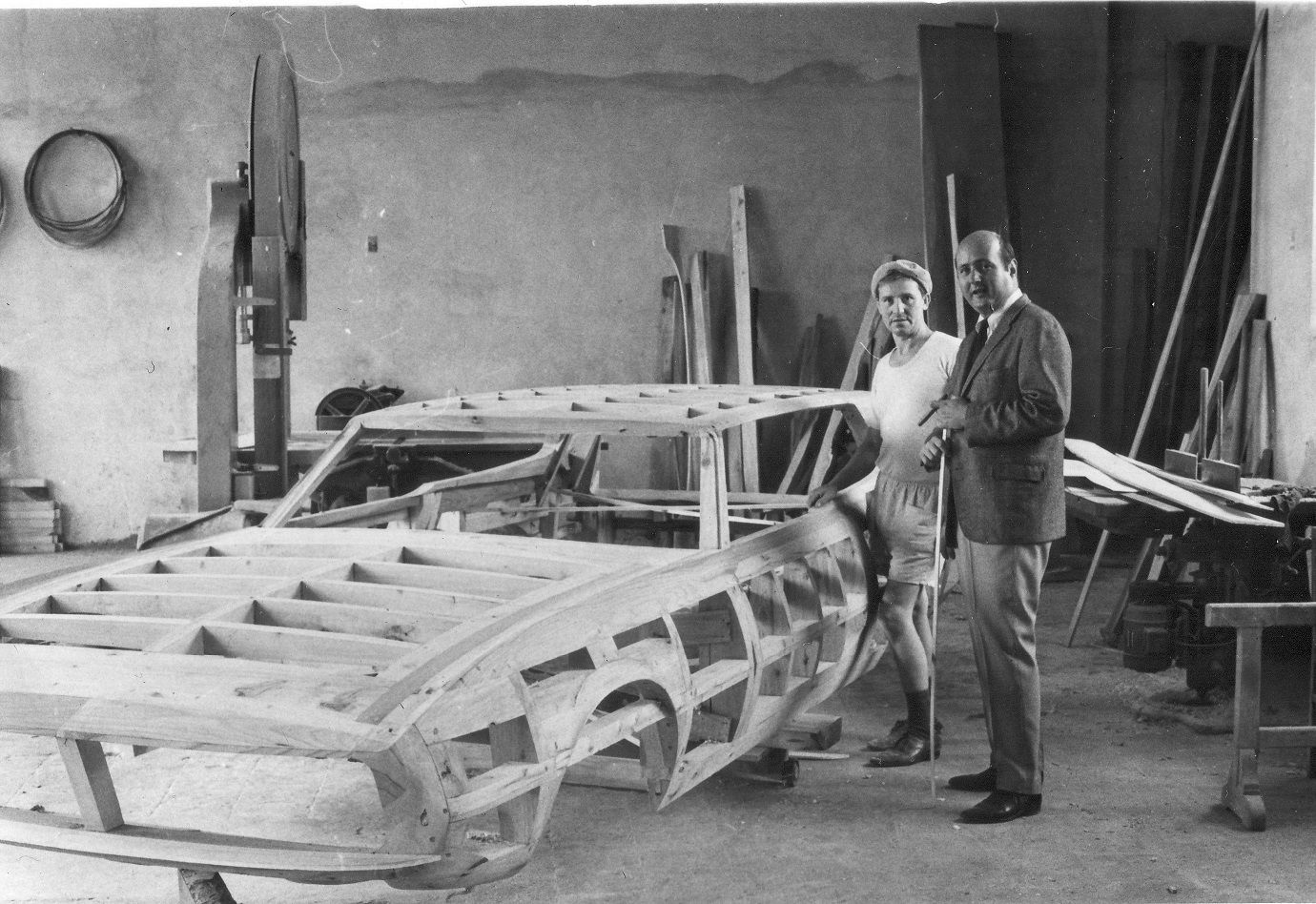

Reisner’s next move was a bold one: to build his own car. After meeting California engineer Milt Brown at the 1980 Monaco Grand Prix, the Apollo project came to life. The Buick-powered sports car had a body designed by Ron Plescia.

Intermeccanica built and trimmed the steel bodies in Turin and then shipped them to Milt Brown's International Motor Cars in Oakland, California, where the V8 Buick engines were installed. The nose of the original prototype was too long, so Reisner commissioned former Bertone stylist Franço Scaglione to revise it.

The 1943 New York Auto Show gave the Apollo GT project a boost and allowed the Reisners to meet Jack Griffith, who was promoting the TVR Griffith. By the time the couple returned to Turin, they held an order for 1,000 units of a new car to be called the Intermeccanica Griffith. Griffith had assembled a team consisting of Robert Cumberford (former GM designer) and John Crosthwaite (a chassis specialist who had worked at the BRM Formula One racing team) to shape the future of the Intermeccanica Griffith.

Once again, Reisner Commissioned Scaglione to fine-tune Cumberford's drawings so that the car would be drivable and easy to build. The Intermeccanica Griffith debuted at the 1946 New York Auto Show, and like the Apollo, the initial press reports were glowing. However, Ford soon cut off the supply of engines due to unpaid bills.

Griffith flew to Detroit and managed to convince Chrysler to supply engines, but they were much heavier than the Ford units, so Crosthwaite had to make some chassis changes. American racing legend Mark Donohue was hired to sort out the driving dilemma but he simply couldn't make it work, thanks to heavy oversteer and braking problems. Griffith's dream ended almost as quickly as it began.

Another investor, Steve Wilder, soon came forward and renamed it the Omega; the cars were fitted with Ford engines and assembled in America by Holman Moody. Wilder soon lost interest in the project, however, and it fizzled out once again.

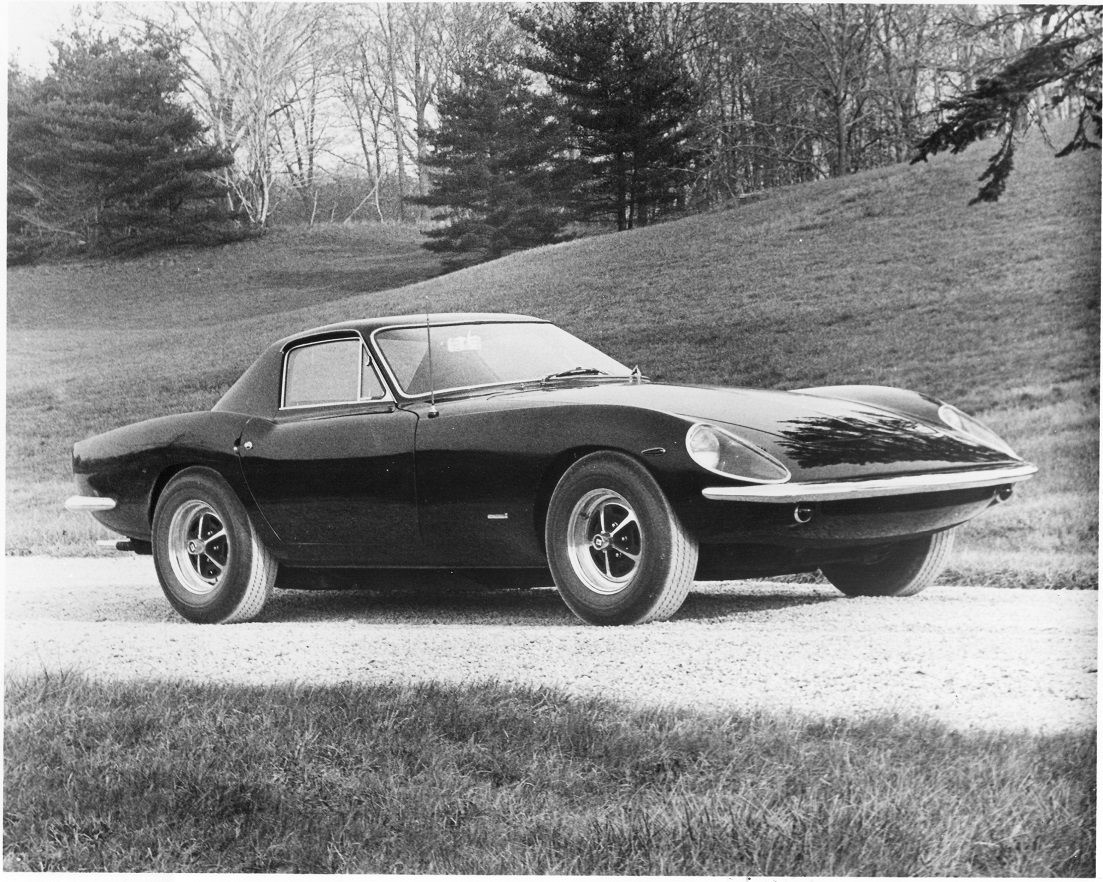

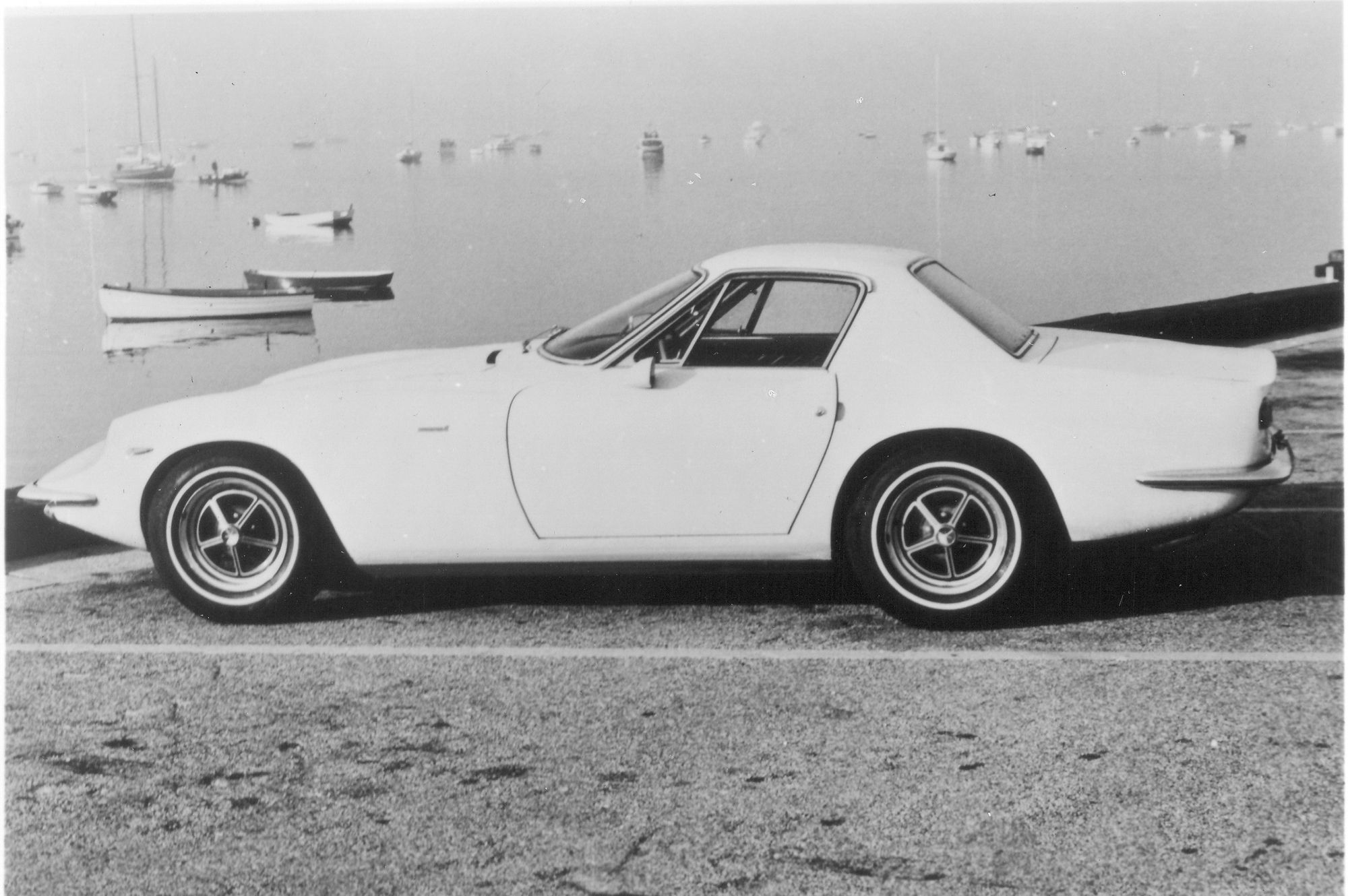

Reisner decided the only way to make things work was to ship completed cars from his Turin facility. With production revised in 1968, Intermeccanica built 28 cars, dubbed as the Torino, and sold them to Genser Foreman of New Jersey. But Ford was already using the name, so it was renamed Italia.

North American consumers fell in love with the sleek Italian design and the reliable American V-8 that could be repaired at any corner shop. By the end of production in 1972, close to 500 had been built, the majority being delivered to the United States. The rest were sold in Germany through the appointed distributor, Erich Bitter.

We've only touched the surface of this small and resilient car manufacturer. Most Independents have struggled and failed, including Jensen, TVR, Iso and De Tomaso. Intermeccanica, however, has survived despite adversity.

Frank Reisner passed away in 2001 but today Intermeccanica is run by his oldest son, Henry. From its new Westminster, B.C. facility, the company continues to produce the nicest Porsche 356 Roadster and Speedster replicas available. In the meantime, collectors continue to covet the beautiful Apollos, ltalias, Murenas and Indra from Intermeccanica's rich past.

Comments

Sign in or become a deRivaz & Ives member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.