The Sipani Dolphin Adventure—Part 2

Images: Vrutika Doshi, R K Sipani, Zuhin Abdul, Gedee Car Museum & Vicky Chandhok

So how could R K Sipani enter the car industry despite the licence Raj system?

Even if the licensing for the manufacture of two- and three-wheelers had been liberalised in the early 1970s, the car industry was still highly ‘controlled’, with the permission to make cars restricted to India’s Little Three: Hindustan Motors, Premier Automobiles and Standard Motors.

Yes, licences had also been given to a certain Madan Mohan Rao and a certain Sanjay Gandhi way back in the early 1970s… but the former disappeared soon after he received the licence, and the story of the latter… well that’s worth another lengthy article sometime.

For our story what we need to remember is that, on 23rd June 1980, Sanjay Gandhi crashed his Pitts S-2A light aircraft in Delhi. He was killed instantly. Barely eight months later, on 24th February 1981, Maruti Udyog limited was incorporated, to keep alive the dream of Indira Gandhi’s favourite son.

As the Maruti story was unfolding, R K Sipani was doing his own research. Enquiring with the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT), Sipani found that if the total investment was within 58 Lakhs (or $100,000 then), no licence was required, if the cost of imported parts remained less than 30 percent of the eventual value of the product.

With such constraints as limitations, R K Sipani signed a techno-commercial collaboration with Reliant Motors, that allowed him to import the tooling for the body and other parts of the Reliant Kitten, as well as the jigs and fixtures to make the chassis.

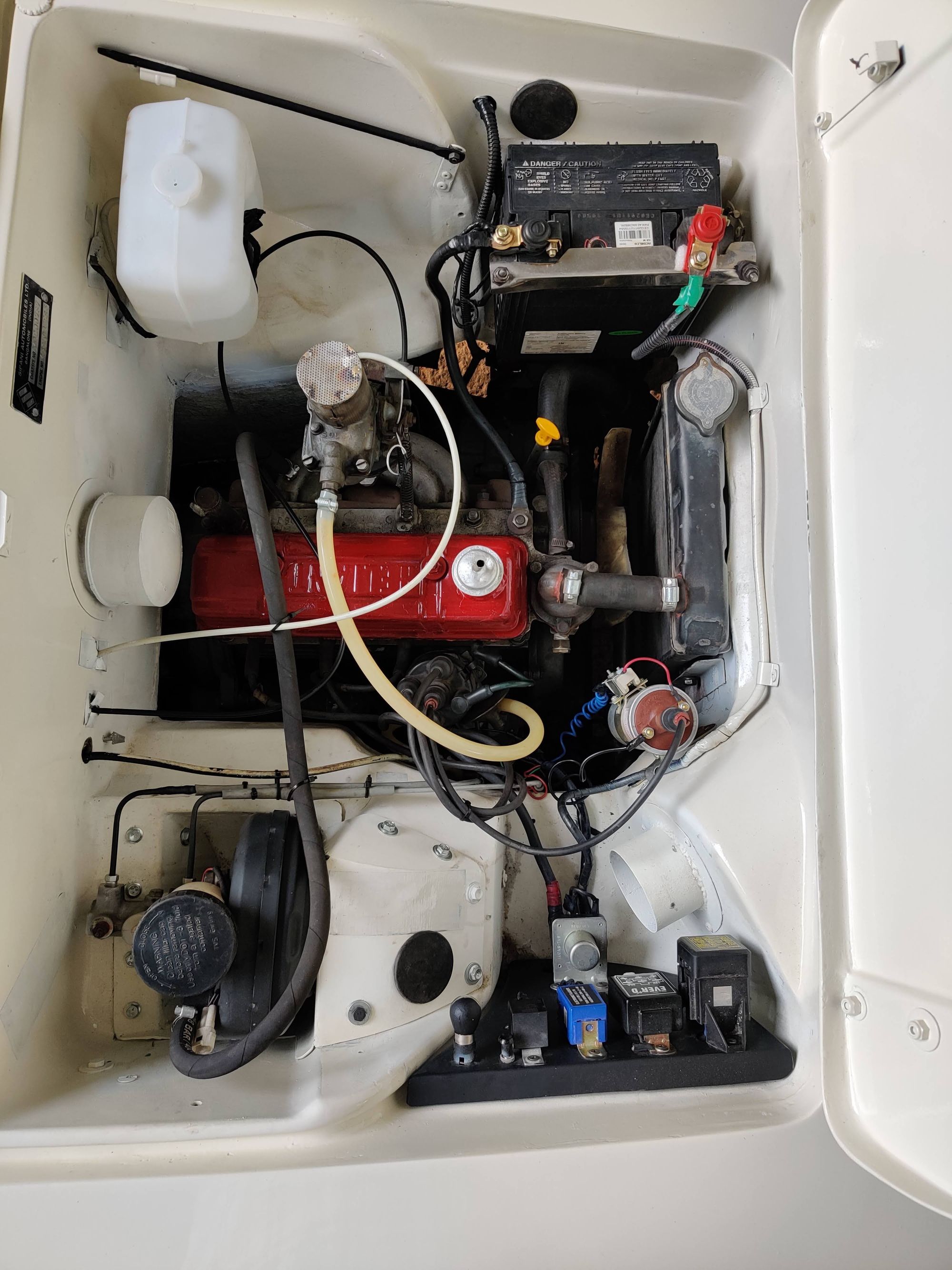

With the bodies and chassis indigenized, only the engine and transmission needed to be imported, which, in value terms, was safely within the 30 percent restriction rule prevailing in India then.

The Sipani Automobiles plans to make the Reliant Kitten in India received governmental clearance in 1981 itself. It is quite possible that the government didn’t come in the way, as it was keen to get Maruti Udyog going and giving Sipani a licence was a sop to criticisms in connection with the government’s apparent bias towards the former.

By late 1981, Sipani had imported two cars, and one was on display in Bombay (now Mumbai) at Gohil Motors, at their Mahim showroom, which this author remembers examining at length. Compared to the Hindustan Ambassador and the Premier Padmini, the new car from Sipani, badged Dolphin, looked much more modern and decidedly cuter.

Given the simple technology involved, production of the Sipani Dolphins started in 1982. Choice of colours included a simple white, a lovely light blue, and a flamboyant (compared to what was available then in India) red and a bright yellow.

Priced at Rs 65,000—when the Ambassador and Padmini were a tad above Rs 75,000—the Sipani Dolphin seemed a decent deal. Even if the limitations of just two doors kept away many of the buyers, the sales of the Dolphin took off modestly well by 1983.

But then the Maruti 800 arrived, in late 1983/beginning 1984. Four-doors, a metal body, and a price tag of a tad over Rs 50,000 changed the market dynamics altogether.

Of course, the initial premium (of almost the base price of the car) and the lack of easy availability of the Maruti 800 kept sales going for the Dolphin. But by 1987–88 sales had tailed off completely.

In the meantime, by 1985, the Dolphin’s 848cc four-cylinder petrol engine and four-speed transmission had been localised completely, and the car was fully made in India (unlike the Maruti 800, which took a very long while to meet the phased manufacturing programme for complete localisation).

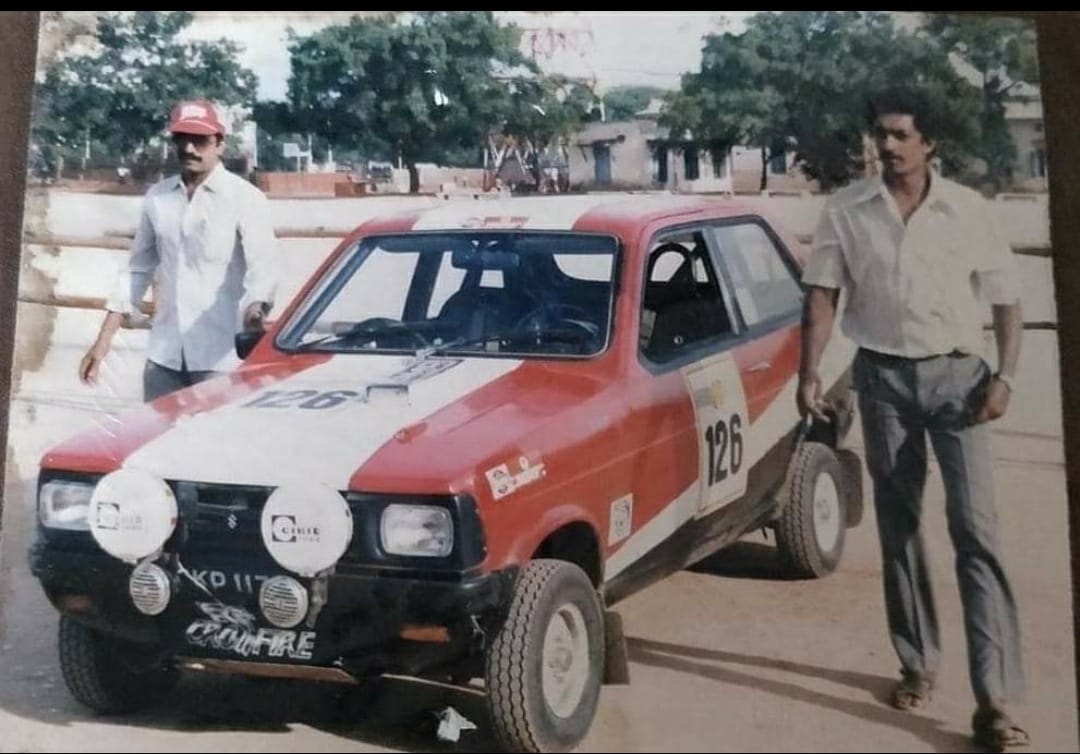

At the same time, the Dolphin was building up quite a reputation in the Indian motorsports arena.

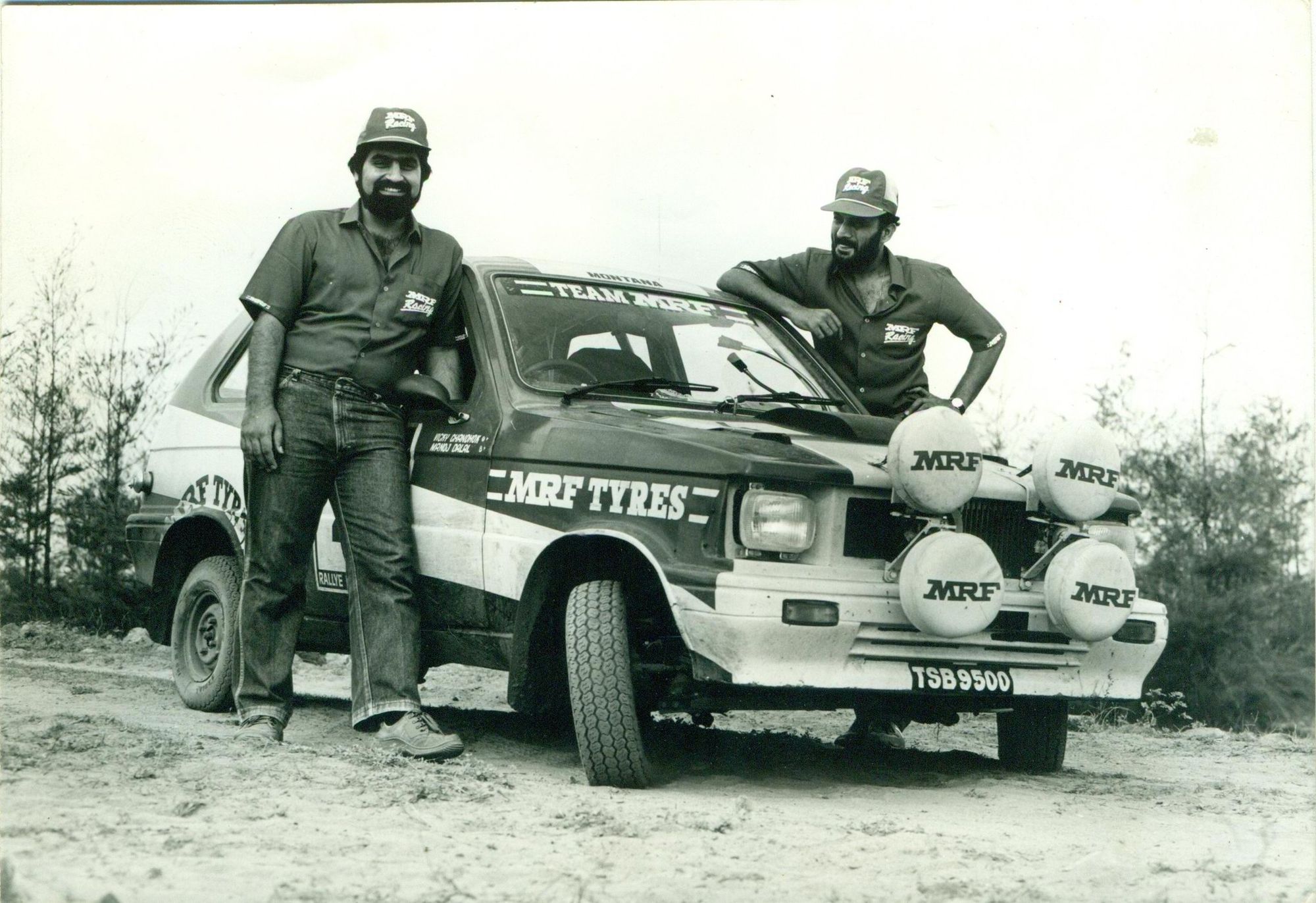

One of the earliest outings of a Dolphin in racing was at Sholavaram, when a Vicky Chandhok-prepared Dolphin was raced very successfully by Manoj Dalal. Soon that was joined by a Group 2 Dolphin with a Ford engine, prepared by S Karivardhan and raced by C K Jinan.

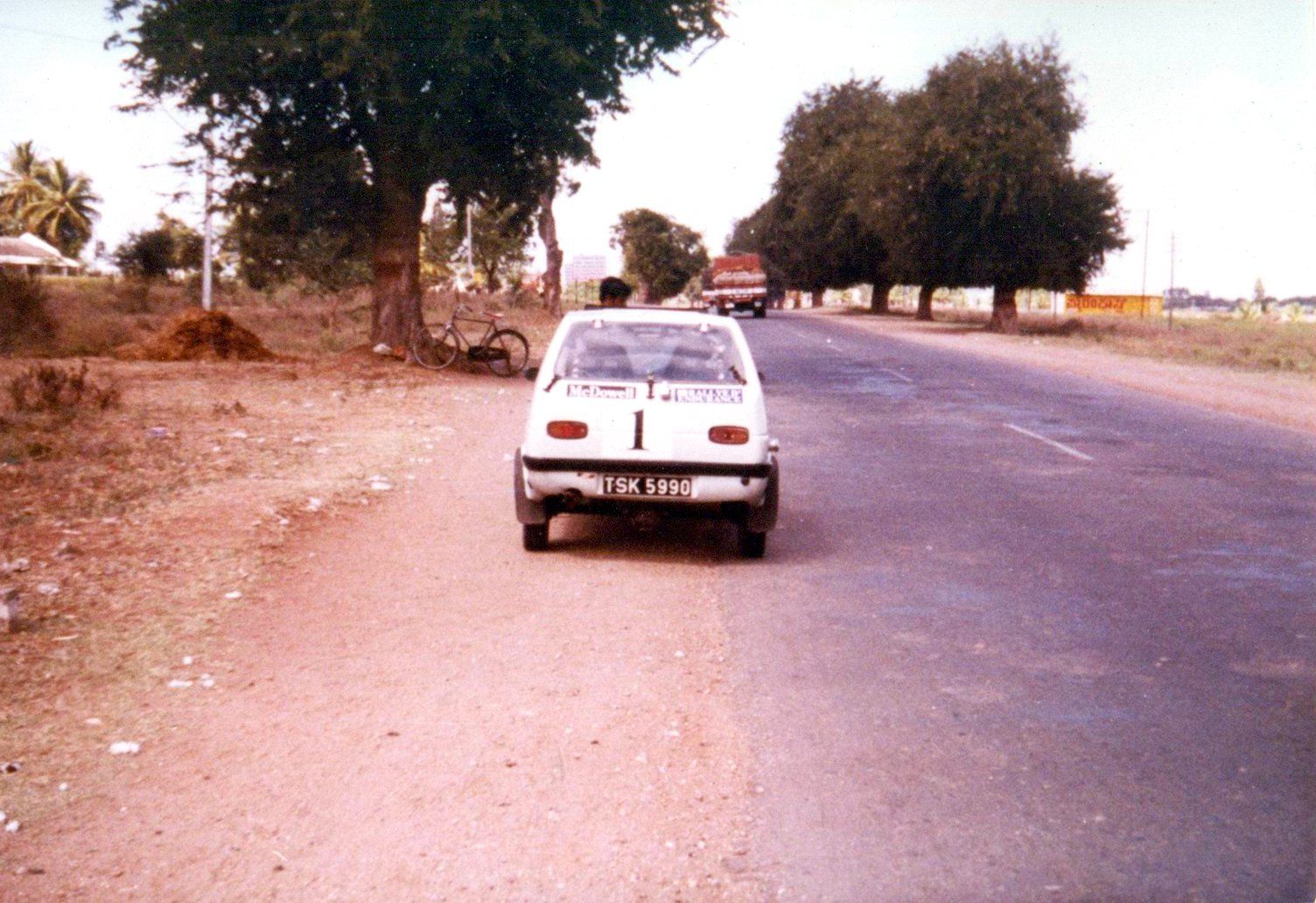

Most famous of all the speedster Dolphins was the black and gold one prepared to Group 2 specifications, with McDowell emblazoned boldly on the sides, which was raced by Ravi Gupta (and rallied by Vicky Chandhok at the IASC several times).

The Dolphin proved to be a sensation at rallying too, when Rajiv Rai navigated a car entered at the South India Rally. “It was a racing car with a skin,” is how Chandhok described the Dolphin. “If the road conditions were good, the Dolphin was unbeatable. At the same time, it was very fragile too, specifically the rear axle and differentials.”

Dolphins went on to win the South India Rally three times!

“We managed to master the art of replacing the rear axle, down to seven minutes,” confesses Chandhok, who was not only rallying Dolphins, but was a dealer for the car in Chennai.

Running rear axle ratios of 3.23, 4.11 and 4.58 depending on the rally sections, and changing them at every service ensured competitiveness, making the Dolphin a very effective rally weapon until the advent of the Maruti Gypsy.

But all this didn’t help sales one bit. So, in 1989, Sipani came up with the four-door Montana, which was a heavily reworked Dolphin with two additional doors, and the option of a diesel engine. There was some initial interest, but sales of the Montana remained modest too.

A coupe derivative of the Dolphin was also developed by Sipani Automobiles, but the styling was unconvincing, and the car remained a one-off.

In around five years of production, an estimated 2,500-odd Dolphins seem to have found buyers in India. In comparison, Reliant managed to sell 4,074 Kittens in a seven-year model run from 1975 to 1982 (plus, another 1,600 of the Reliant Fox—the Mebea Fox in Greece—which was a redesigned pick-up derivative of the Kitten).

Even a two-seater sportster version of the Kitten was designed, and a few made. And which had yours truly developing his own sportster… but then that’s another story for another time…

Of course, this story wouldn’t be complete till we explain why we have such pretty and fresh images of the ‘four-wheeled Badal’, which, in a fortuitous set of circumstances, has been ‘saved’ by Shreeram Parulekar, from Pune.

As to how that prototype landed up in Pune is not known. But Parulekar, who is an enthusiast for the rare and the unusual in the Indian context, heard about this car being on sale with a dealer in Pune.

When he saw the car, he recognised it for what it was. The dealer also realised that he had his hands on a real rarity and was therefore asking for a prohibitive price.

It took a few years of constant reminders and negotiations before the dealer agreed to sell the car for a substantial sum “worth a few Dolphins,” admits Parulekar.

But it has been worth it, as today, post the restoration, Shreeram Parulekar has an important piece of India’s automotive history.

Comments

Sign in or become a deRivaz & Ives member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.