The Mystery of Dorothy Patten & her 1938 Peugeot 402 Darl’mat Competition Roadster – Part 2

Text: David Cooper & Peter Moss Images: David Cooper

Following from the first part of this story, published yesterday on deRivaz & Ives Magazine:

Becoming a World-Class Race Driver (1906-1934)

The elder Dorothy Patten’s actual history is a tangle of facts, tall tales and speculations that only now can be documented from official records, conflicting society and motoring magazines, and careful study her racing scrapbook. Alice Minnie Patten was born on 30 December 1906 in Queensferry, Flintshire in North Wales. Her father, Arthur Patten, was, in 1901, a joiner’s labourer, living with his wife and four children, including a seven-year-old daughter Dorothy. We found Alice Minnie’s birth certificate: Arthur is recorded as a check weighman for John Summers and Sons at the nearby Shotton Steel Works. He did not make enough in this work to support his family of ten. Records from the St. Mark’s County Home for girls, run by the Waifs and Strays Society, show Alice Minnie in residence from the age of 11, the minimum age for acceptance in the Home. The St. Mark’s County Home prepared girls for domestic service with training in menial housework, laundry work and cooking. This was not Alice Minnie’s destiny.

In her teens or early twenties, Alice Minnie reappears, curiously now using her oldest sister’s name Dorothy as a professional name, though her personal friends called her Minnie. We do not know the fate of the oldest sister, other than her birth in 1894 and that she had left home before she was 17 and was never mentioned again in any of the records we could find.

The new Dorothy somehow escaped both poverty and her low social class. This was a remarkable accomplishment in pre-war England, where the system was designed to repress upward social mobility. She traveled to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1932, perhaps as a companion to a wealthy friend. One year later, in 1933, Dorothy reappears in an Alvis race car competing in the Alpine Trials in the company of upper-class racers. In the early 20th century, there were a small number of very good female race drivers, who usually competed on an equal basis with the men. Some, like Dorothy and French driver Hellé Nice, rose from extreme poverty. It took great talent, considerable resources, and a willingness to challenge conventions to join this select group.

As reported by Motor Sport, Dorothy Patten drove the Alvis in both the 1933 and 1934 Alpine Trials, whose course changed every year. These challenging events give a good indication of her driving skill and tenacity. These five-day trials (‘Coupe Internationale des Alpes’) were some of the most difficult events in motor racing. They involved timed ascents of most of the great Alpine passes at high average speeds. Repairs and maintenance to the vehicles were restricted. The pace was fast on steep winding roads, often in adverse weather conditions. Even in tight corners next to precipitous drops, entrants had to give the right of way to Swiss post-buses. Manufacturers considered the Alpine Rally a test of the quality and mettle of their automobiles. One writer said their sole purpose was to destroy a car.

The 1933 trial was considered particularly severe. Dorothy was one of four women drivers from Britain of a total 132 entries. She competed in the Glacier Cup competition, which was for individuals rather than marques. She was penalized on the fourth day and finished 14th in her class in the Glacier Cup competition. But she was one of the finishers.

How and when did she learn to drive race cars in these severe trials? And where did she get her racecar? From race entries, we know that H.H. Porter-Hargreaves raced an Alvis Speed 20 the year before in the 1932 Alpine trial. The next year he acquired and raced a Frazer-Nash. It appears to be his Alvis that Dorothy Patten drove in the two Alpine Trials and later in the Monte Carlo Rally.

It required a different social background to move into this much higher class and fit into the racing crowd at Brooklands and elsewhere. Dorothy created a new life story, regularly lowering her age and claiming a deceased army colonel with the same last name, Henderson Patten, as her father.

Baroness Dorothy Dorndorf (1935-1946)

1935 was an important year in Dorothy’s life—both for romance and for racing. In January of that year Dorothy Patten drove the Alvis Speed 20, sometimes wrongly reported as an AC, on the Monte Carlo Rally, where she met Baron Rainer von Dorndorf. Rainer Dorndorf came from a wealthy industrial Jewish family, long established in Germany. Rainer was an outspoken opponent of the Nazi government and fled Germany in 1933 shortly after the Nazis came to power. This began a long odyssey which ultimately led him to settle in Ireland.

Dorndorf ’s friend Fritz von Richthofen, a cousin of the Red Baron, drove a BMW 328 in the same race. Fritz had convinced his shy friend Rainer to approach the outgoing and feisty party girl Dorothy Patten after the race. Rainer and Dorothy were married that summer and settled in London. Rainer was 22, and according to the marriage certificate Dorothy was 23. She was not: she was 28. Dorothy used the title Baroness Dorndorf—quite a step up in social class.

Soon after their marriage, the couple acquired a brand new 20/90 British Salmson. This was a purely British model with no French equivalent. It was powered by a six-cylinder 2½-litre twin overhead cam engine, capable of 90 mph. Perhaps no more than 15 examples of this rare model were built up through 1939. Dorothy and Rainer campaigned the Salmson from 1936 in active competition and her racing successes were used in the Salmson company’s advertising.

Their next race car was a complete departure from the rugged six-cylinder Salmson. In September 1938, the couple ordered the first Darl’mat imported into England, sourced through Tom Knowles, the London-based Peugeot importer.

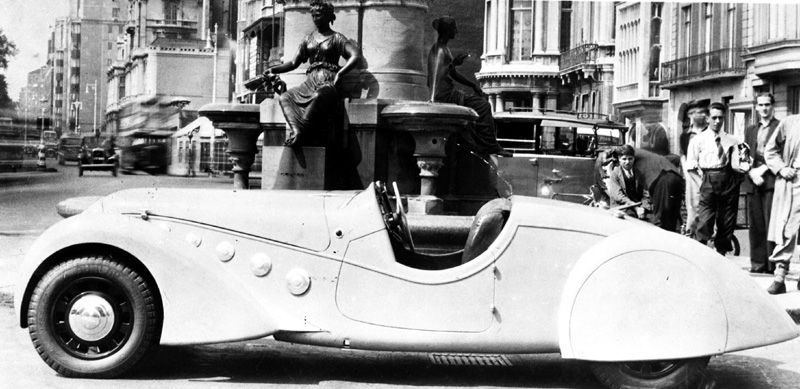

Émile Darl’mat (1892-1970) was a licensed Peugeot dealer on rue de l’Université in Paris from the early 1930s. Believing that Peugeot needed a sportier car to compete in the market, he commissioned designer Georges Paulin and coachbuilder Marcel Pourtout to craft an elegant and aerodynamic roadster body for the Peugeot chassis and drivetrain. He called it the Peugeot Dar’mat 402 Special Sport. One example raced at the 25 hours of Montlhéry at an average of 139.282 km/h.

The Darl’mats were lightweight and nimble cars with high-revving four-cylinder engines, developing 70 bhp at 4,500 rpm at a cost of £495, not including the optional Cotal gearbox. This was equivalent to $2,475 USD at the 1938 exchange rate, more than the price for a Jaguar SS100 Le Mans 3½-litre two-seater. Only 104 Peugeot Darl’mats were built in 1937 and 1938.

Dorothy’s car was one of two right-hand drive Peugeot 402 Darl’mat roadsters ever built, and the only survivor. It was featured in London Autocar magazine in its original white color. Dorothy had the car repainted a French blue and had the upholstery redone in a dark blue leather. Dorothy & Rainer had the car fitted with special competition features, including a 2.0-liter high compression engine, special Memini carburetors and large competition brakes.

The Dorndorfs actively competed in ten events in the Darl’mat before WWII broke out in September including the Paris-St. Raphael Rally, the 12-hour race from Paris to Monthlery and the Welsh Motor Rally.

In a wartime article, Dorothy Patten confirmed the fate of the car during the war: “It is now laid up awaiting better times.” A mere six weeks after the outbreak of the war, Rainer Dorndorf was declared a non-refugee enemy alien and was interned, along with many of his fellow-countrymen, on the Isle of Man. Ironically, like many upper-class Jews, he was not German enough for the Germans, but too German for the British. Ultimately the British decided Rainer was an alien but not an enemy. He was released to house arrest with his sister in Ireland for the duration of the war.

During Rainer’s internment, Dorothy asked for a divorce, which was granted at some time between 1941 and 1946, but probably between 1942 and 1943. Dorothy kept the Darl’mat in the settlement. Rainer stayed in Ireland after the war, becoming a farmer and, when racing resumed, he acquired and competed in a BMW 328.

Post-War (1947-1975)

In 1947 Dorothy married David Allan Apsley Treherne, a Captain in the Green Howards. Treherne was 28, and this time the marriage certificate shows that Dorothy used her birth names of Minnie Alice, gave her true age of 40, and confirmed that she was the divorced wife of Rainer Dorndorf. Treherne was section commander of a glider squadron stationed in Arnhem during the war and had been injured in a glider crash.

After WWII ended, Dorothy returned to the racing circuit in the Darl’mat, now repainted in a dark color. She competed in four races, but the poor quality of the post-war fuel did not work well in the Peugeot’s high compression engine and the car was not competitive. Dorothy retired from racing in 1948. She died on 14 November 1975 at the age of 68. In typical Dorothy Patten fashion, the death certificate subtracted 10 years from her age.

The Darl’mat after its race career (1957-2024)

The elder Dorothy Patten sold the Darl’mat in 1957. Peter Rose acquired it in 1960 and reportedly drove it actively in Club events. When Rose died in 2009, the car was acquired by the collector from the Netherlands, leading to its restoration by Tony Paalman.

Based on the newly researched provenance information, Cooper Technica re-restored the Darl’mat to the way Dorothy and Rainer raced it before WWII. It now includes the badges Dorothy Patten had on the car. It is painted in nitrocellulose lacquer in the same light blue color Dorothy Patten chose. The car is fully documented with its original chassis and engine.

After completion, Dorothy Patten’s Darl’mat was shown at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance in August 2021 and has been featured in several articles and in a forthcoming podcast this year.

Rare & Unique Vehicles Magazine

This article was revised and adapted from Rare & Unique Vehicles Issue 9, Winter 2023 https://rareandunique.media/product/ruv-vol-3-no-9-special-theme-provenance/. Reprinted by permission.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

David Cooper is a historian and restorer specializing in pre-WWII French and Italian cars. With workshops in France and Wisconsin, he is known for his commitment for authenticity and historical accuracy. David is also the Associate Editor of Rare & Unique Vehicles magazine.

Peter Moss is a chemical engineer and industrial consultant with a passion for motoring history. A longtime member of the Society of Automotive Historians in Britain, Peter has published many articles and books on Rolls-Royce and Bugatti motor cars.

Comments

Sign in or become a deRivaz & Ives member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.